Unity for Beginners: Flappy Bird!

This sheet is designed to be a pretty structured walkthrough of game development in Unity.

We will be making our own version of Flappy Bird - this task is pretty much the game development equivalent of the “Hello, World” programming exercise. It should equip you with the prerequisite knowledge you will need to create most kinds of games you might want to work on during the upcoming game jam.

The completed code for this project is available on GitHub.

The instructions are very slow and thorough in the earlier sections so as to give you a strong understanding of the most basic Unity functionality, but as the workshop progresses the pace will pickup! If you’re confident in the earlier sections, feel free to skim through them, and if the later parts are a bit unclear please feel free to ask for help.

There are some notes strewn throughout the sheet which aren’t necessary for progression, but may provide some hints or explain tangential information in better detail. There are also tasks which will prompt you to do some programming without much assistance.

Throughout the workshop, I assume that everyone will be using the lab machines. If you aren’t, you’ll need to go through the instructions here in order to install the required software on your machine.

Setup

First, we need to create a project. We will be doing so through the Unity Hub, which is a piece of software that helps you manage your various projects and Unity Editor installations.

- Click on the start menu (bottom-left of the screen) and open “Unity Hub”, which is located near to the bottom of the list of applications. If Unity Hub buffers endlessly at this point, it’s probably best to switch machines (I don’t know how to fix that).

- Unity Hub will prompt you to sign in or create an account with Unity. Once you have done so, a popup will appear with the heading “This site is trying to open Unity Hub” - click “Open”.

- Unity Hub will prompt you to install a Unity editor, select “Locate Existing Installation” and then “C:\\Program Files\\Unity 2022.3.6f1\\Editor\\Unity”

- Now go to Projects → New Project → 2D (URP). Change the project name and project location to whatever you like by editing the fields on the RHS, and then click “New Project”.

Note: Project templates specify the initial state of the project when you create it. Here we are using the “2D (URP)” project template, which is going to result in our project defaulting to 2D graphics. You may be wondering what the difference is between the “2D” and the “2D (URP)” templates. The URP refers to a particular way of doing graphics that Unity is currently switching to. I’ve chosen to use it because Unity is pushing for URP to replace the old way of doing graphics, so best to learn that. But for this project it won’t make any difference.

Once you’ve created a project, the Unity editor will start up. The user interface might be a little overwhelming at first, but we’ll discuss each element of it as we progress through the workshop.

The Bird

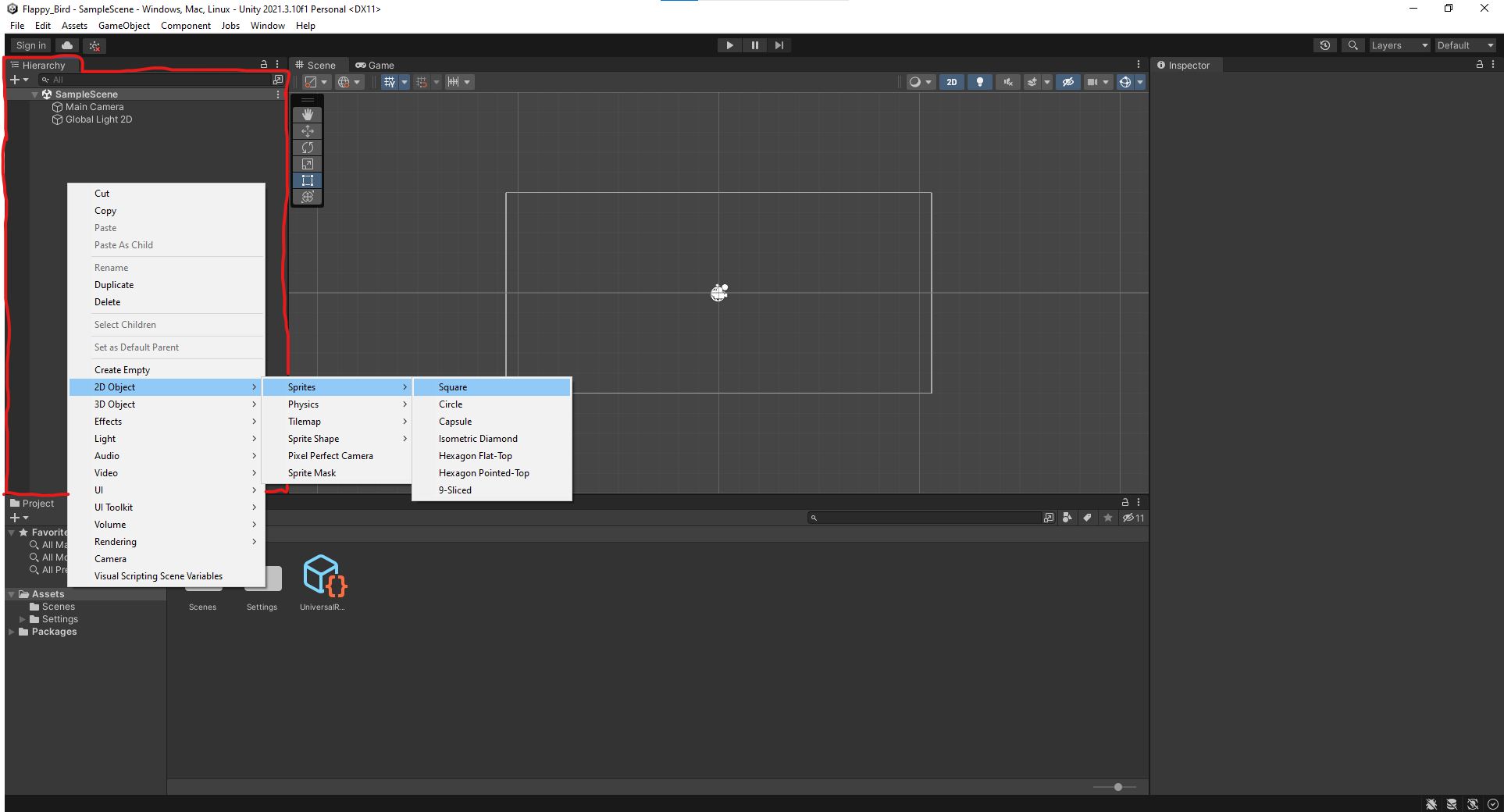

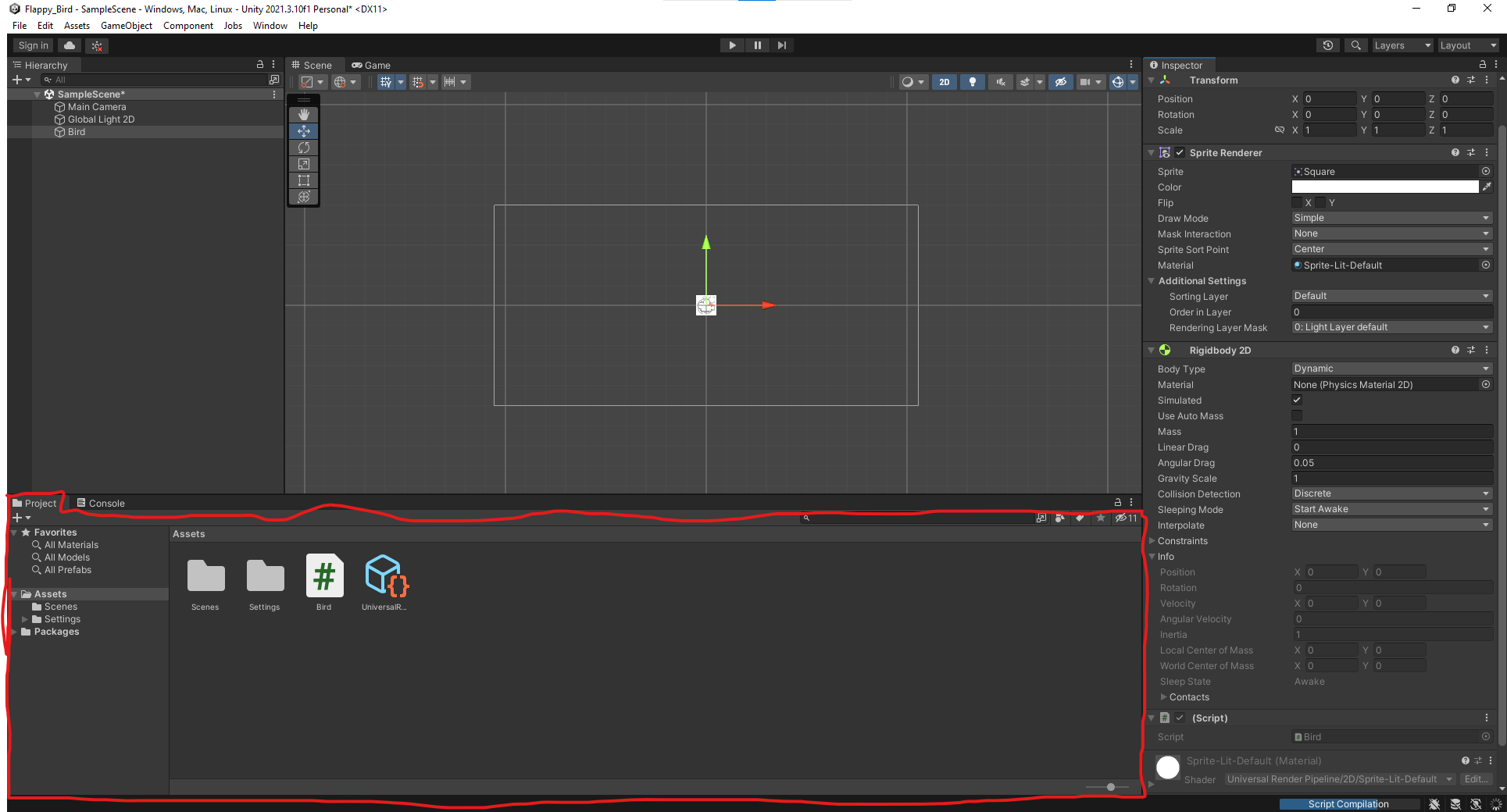

The beating heart of “Flappy Bird” is the flappy bird - let’s start by making one. The hierarchy panel (shown below) lists all of the GameObjects (things) in your game. You’ll see that we currently have just two GameObjects: a camera and a light. The camera defines the player’s view into the game world, and the light will light everything up. Let’s add one more GameObject to represent our bird. Right click on the hierachy panel and select 2D Objects → Sprite → Square.

Note: I lied, the hierarchy panel doesn’t show everything in your game. Games can be split into smaller pieces called scenes for organizational purposes. You can edit one scene at a time. The hierarchy panel shows all the GameObjects in the scene that you’re currently editing. Since this game is small, we’ll keep everything within one scene for simplicity. You can see at the top of the hierarchy panel that Unity has named this scene “SampleScene”.

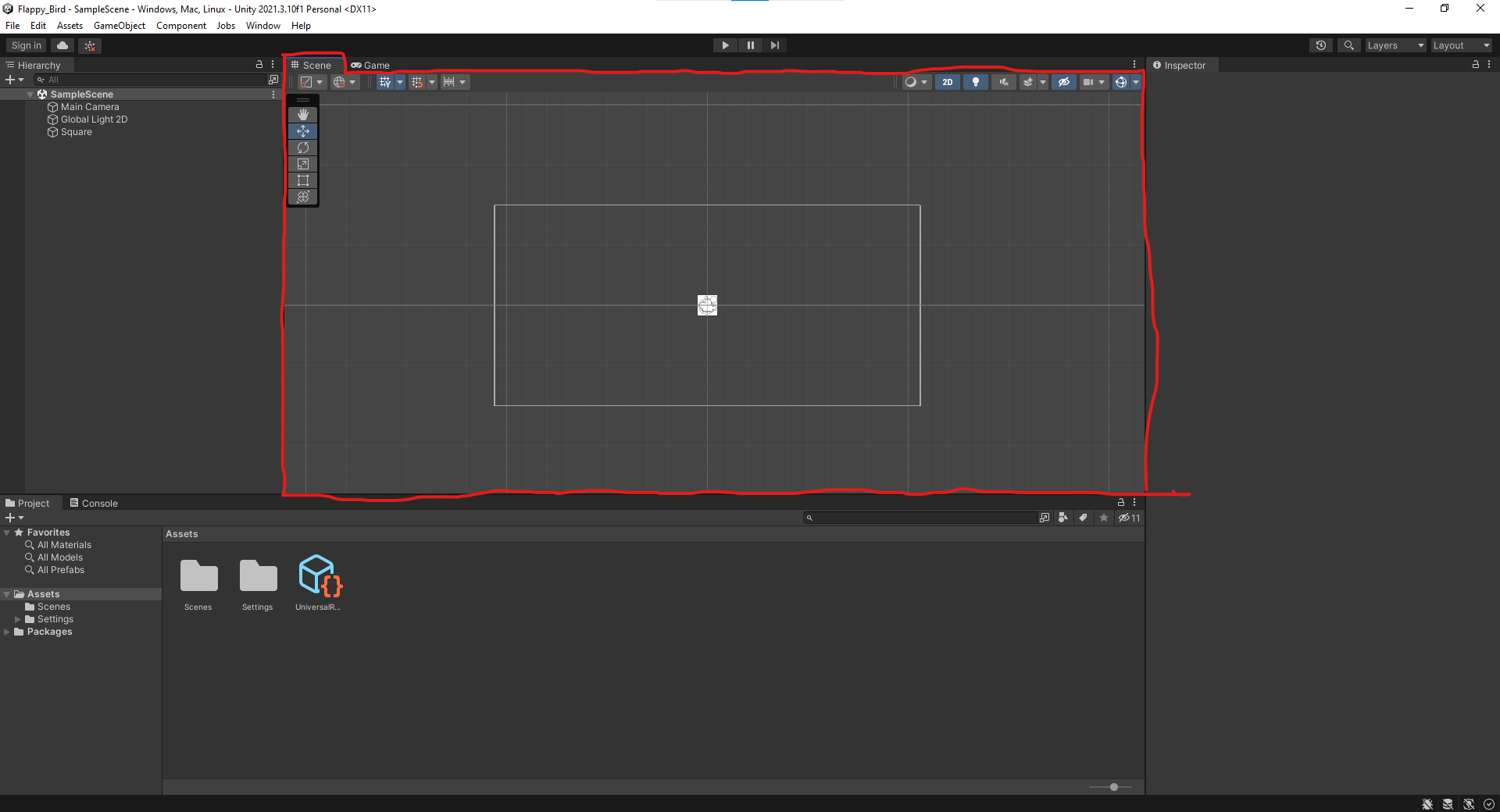

You should now see that a white square has appeared in the scene panel (shown below). This panel shows a visual representation of everything in your game world. You can move the view around by holding down the middle mouse button and dragging. Zooming in and out can be done with the scroll wheel.

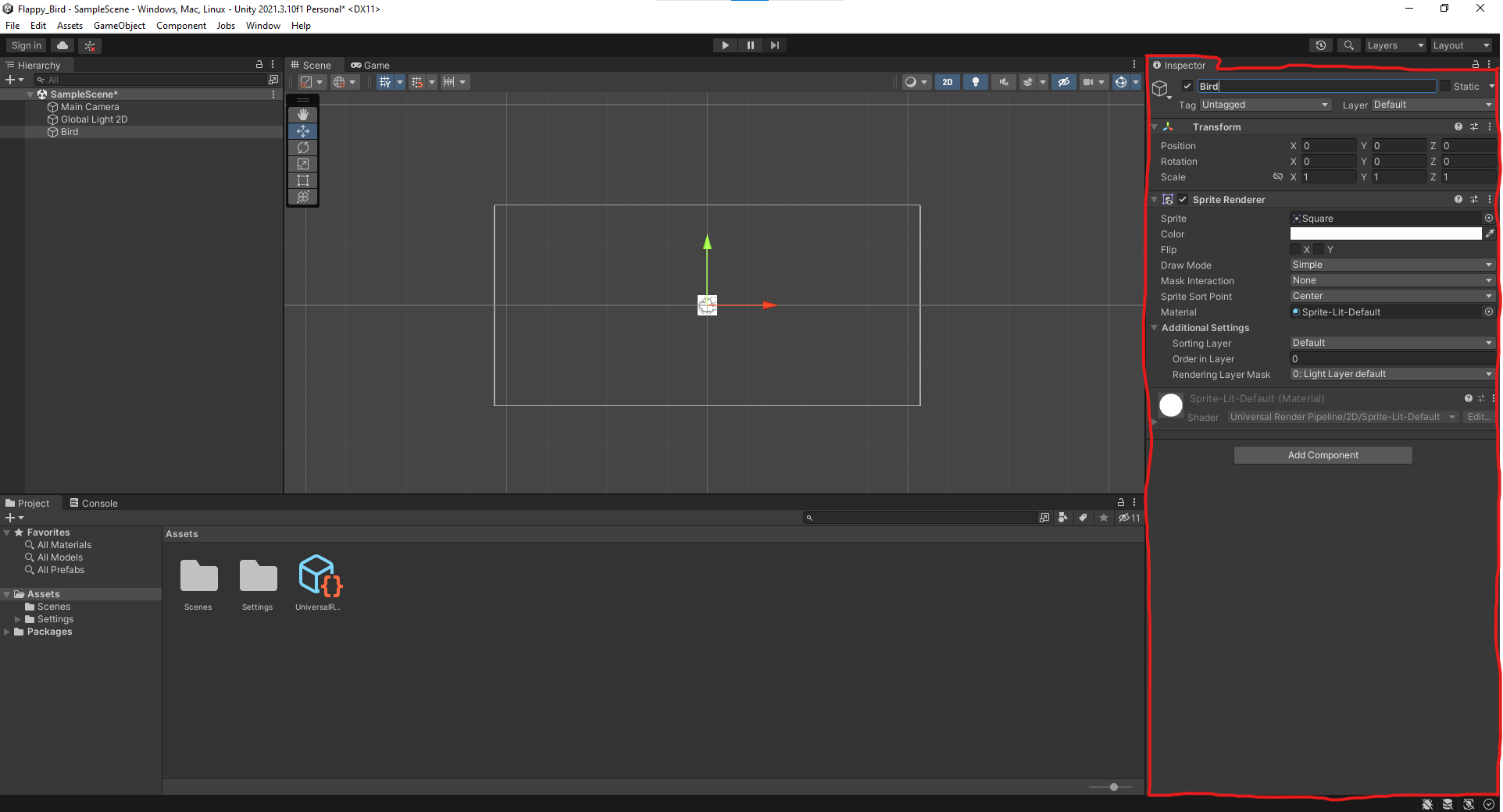

You can select entities by either clicking on them in the hierarchy panel, or clicking on them in the scene panel. Once you have done so, direct your attention to the inspector panel (shown below). The inspector panel contains information about the GameObject that you currently have selected. This information is grouped together into what are called components. You’ll see a “Transform” component that describes where the bird is, and a “Sprite Renderer” component that describes how the bird looks.

Note: You can change the name of our bird GameObject from “Square” to something more descriptive by changing the name field at the top of the inspector panel.

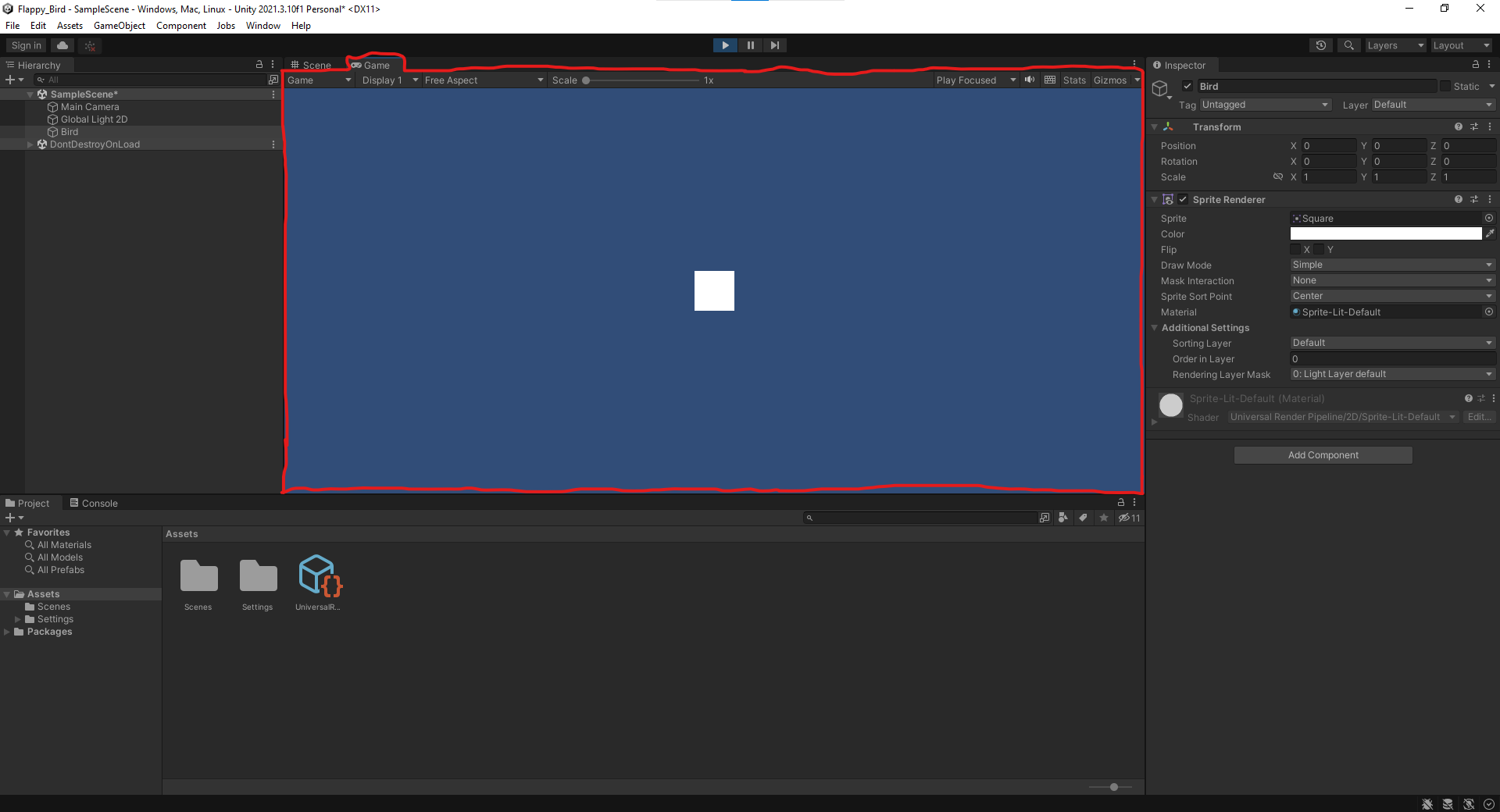

So now we have an object to represent the bird. If we press the play button at the top-center of the screen, we can see how it behaves when the game is running. The game panel (shown below) will come to the fore, you should see that the bird currently does… nothing. You can press the play button again to stop the game.

Note: When you press play, the Unity editor enters “Play Mode”. Any changes that are made during play mode will be reverted when exiting play mode, except for changes to code, which will usually cause Unity to spam you with warnings and errors.

By the end of this section, we want the bird to do the following:

- Fall under the influence of gravity.

- Fly upwards when the player presses a specified button.

- Look like a bird.

- Sound like a bird.

Lets tackle these one by one.

Note: Remember to save your work regularly with the CTRL + S hotkey.

Falling

One of the things that Unity handles is the simulation of physics. We can tell Unity to include our bird in its physics simulations by giving it a component called “Rigidbody 2D”. Do this by selecting the bird, clicking add component in the inspector view, and then selecting Physics 2D → Rigidbody 2D. If you press play again, you should see that the bird is able to fall!

Note: You can change the physical properties of the bird (e.g. its mass, to what extent it’s affected by gravity) by changing the options listed under the Bird’s Rigidbody 2D component in the inspector.

Flapping

Now we need to have the bird fly upwards when the player presses a specified button. This isn’t something that Unity has already done for us, so we’ll have to make our own component by writing a script. Select the bird, click “Add Component” in the inspector, select “New Script” and name your script something sensible. Your script should appear in the project view (shown below), double click on it to open it for editing.

Note: The project panel is simply a file explorer that allows you to view all of the files under the assets folder in your project.

We have three lines at the top which start with the word “using”. They allow us to import and make use of other people’s code. “System.Collections” and “System.Collections.Generic” provide us with common data types that many scripts will tend to use. “UnityEngine” allows us to make use of all of Unity’s functionality.

using System.Collections;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using UnityEngine;

Then we have the class declaration. Classes are used to organize your code by bundling code and data together. The class is named “Bird” to match the name I chose for my script, and the “: Monobehaviour” means that this class inherits from the monobehaviour class. This is to say that our class will not only have all the code that we write in it, but all the code that the original Monobehaviour class had too.

public class Bird : Monobehaviour

{

...

}

Note: In Unity, all components should inherit from Monobehaviour.

Inside the class declaration, we have two empty functions that are provided by Monobehaviour. The first of which is the Start() function, which is called when the game starts.

// Start is called before the first frame update

void Start()

{

}

Then we have the Update() function, which is called at the start of each frame while the game is running.

// Update is called once per frame

void Update()

{

}

Note: Games are essentially a series of still images shown to the user one after another in very quick succession. The user will be shown an image, the game will check for input, perform any necessary calculations, update its state, and then show the user another image. Each of these cycles is called a frame.

We’ll add the following to our Update() function. “Input” is a namespace, which is to say that it’s a keyword we can use to access a bunch of functionality related to user input. “GetKeyDown()” is a function that takes as it’s argument a key (“KeyCode.Space”) and returns a Boolean to indicate whether that key has been pressed down this frame. If that Boolean is true, then we will print the string“Flap!” to the console.

// Update is called once per frame

void Update()

{

if (Input.GetKeyDown(KeyCode.Space))

{

Debug.Log("Flap!");

}

}

Note: You may see references to Unity’s new input system online. This is a more fancy way of dealing with user input that makes it much simpler to do things like button remapping and support for multiple control schemes, but much more complicated to do something simple like this.

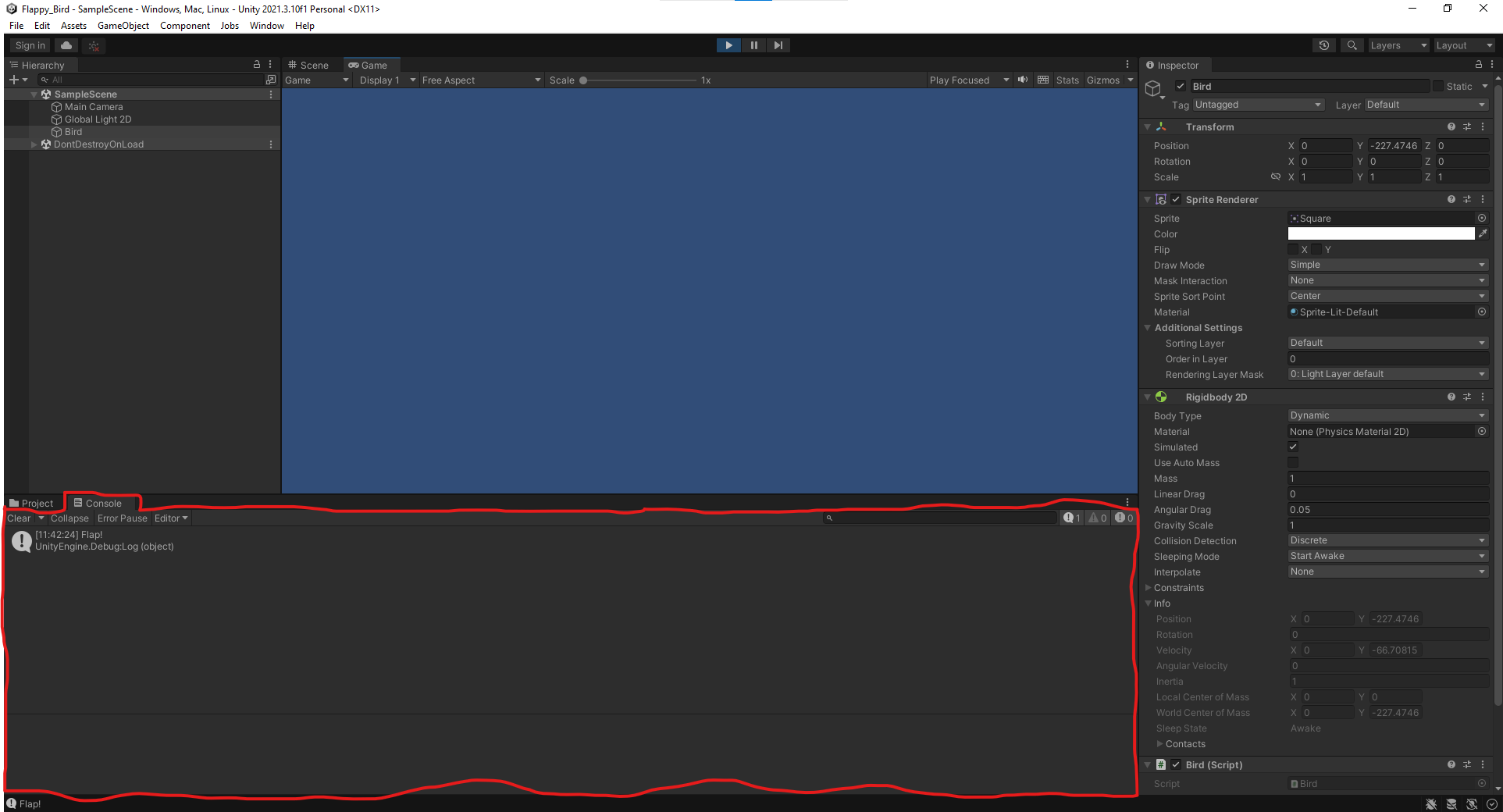

If we press space while the game is running, we should see the following in the Console panel (shown below). To view the console, you’ll need to click on the word “Console” at the top of the project panel.

So we can recognize user input, now we need to interface with Unity’s physics system to make the bird fly up when the space bar is pressed. Our bird’s Rigidbody 2D component has a function that allows us to apply force to the bird. But how do we use this function from within our script? Well, we can use the GetComponent<>() function to access other components on the same GameObject as our script, like so:

var rigidbody2d = GetComponent<Rigidbody2D>();

Then, we can access the Rigidbody2D’s functions through the variable that we’ve created, like so:

rigidbody2d.AddForce(...)

We need to give the AddForce function two arguments:

- A vector. The magnitude indicates the amount of force, and the direction indicates the direction of the force. Vectors can be declared with the syntax “new Vector2(x, y)”.

- A “ForceMode”. This indicates whether the force is an impulse (like the flapping of a bird’s wings), or not (like a thruster).

If we give these arguments, our function call will look like this:

rigidbody2d.AddForce(new Vector2(0, 10), ForceMode2D.Impulse);

Try putting this inside our “if” statement and pressing play, you should see something like this

You’ve now learned about most of the major fundamental concepts in Unity. You can navigate the user interface and the Unity ecosystem. You can create GameObjects and modify the behavior of those GameObjects by adding components. You can even make your own components that react to user input and interact with other components.

The Pipes

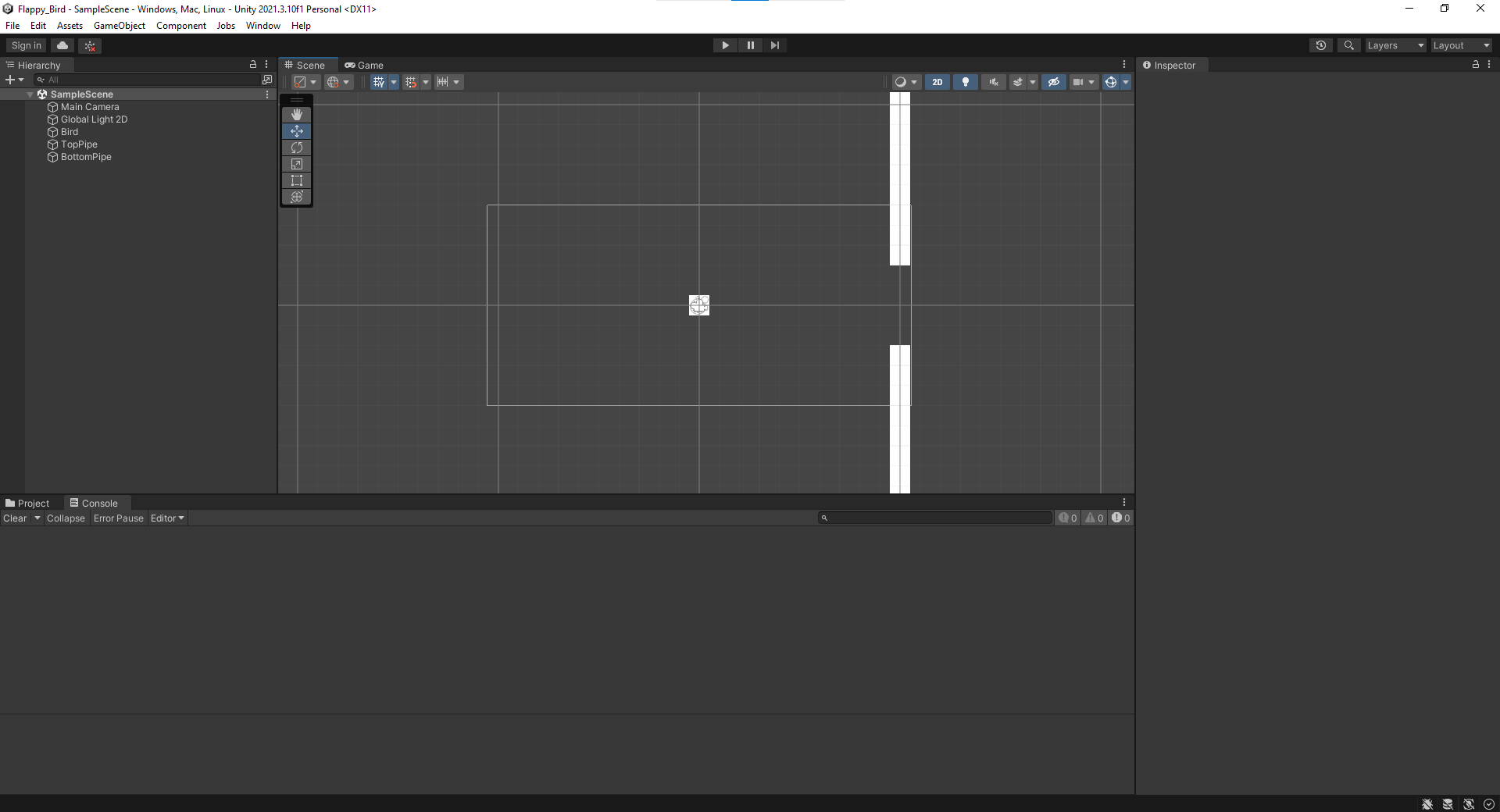

For the pipes, let’s make two square sprites. We’ll elongate them by tweaking the y component of the scale field inside of their transform component. Make sure that there’s some space between them for the bird to fit through - you can tweak their positions by selecting them and dragging the arrows that pop up in the scene view. Aim to end up with something like this:

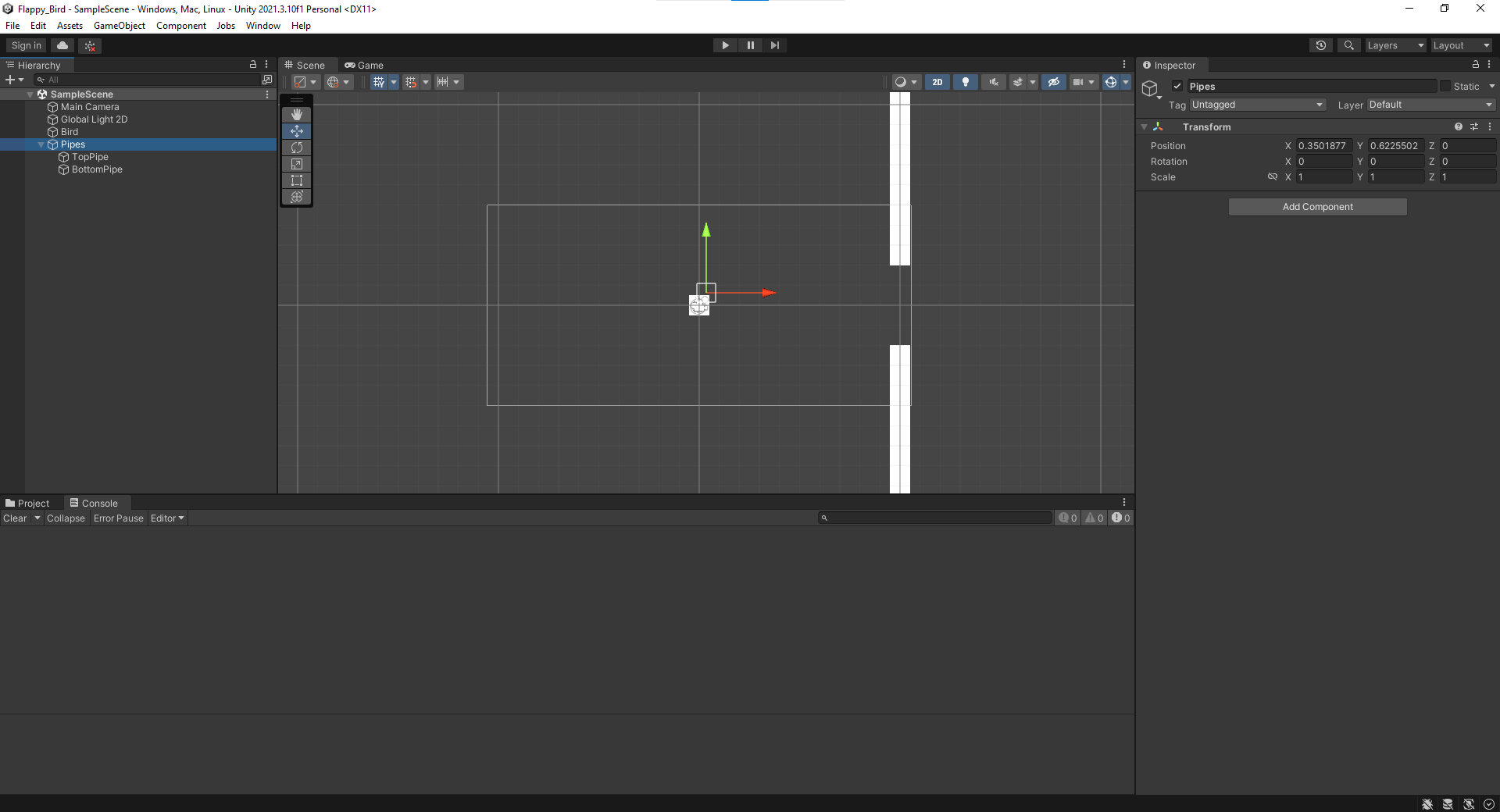

These pipes are currently two separate objects, but in Flappy Bird they always move as one. It would make sense to group the two pipes together, and move the group as a whole rather than each pipe individually. To do this, let’s create a GameObject with no components on it to represent the group. Right click in the hierarchy and select “Create Empty”. Now in the hierarchy panel, click and drag both of your pipes underneath the new GameObject. Your hierarchy should look like this:

In this situation, it is common to call the empty GameObject the “Parent”, and the grouped GameObjects “Children”. Whenever the parent moves, the children will move too.

Task: Using what you learnt from making the bird move, try making the pipes move from the right side of the screen to the left. They should start moving when the game starts, and they should not be affected by gravity. Aim for something like this.

Now we don’t want just one set of pipes, we want many. There is a way for us to essentially copy and paste the pipes that we’ve already made whenever we need new ones. Drag the pipe parent from the hierarchy panel to the project panel. By doing this you have made what is called a prefab. This is a little like copying something onto your clipboard. You can edit the prefab by double clicking on it, and you can stop editing it by clicking the back arrow near the top of the hierarchy view.

Note: Whenever you make changes to the prefab, those changes are mirrored in all the places you use the prefab.

Now we need to create a new game object that’s in charge of pasting our prefab into the game world. Create an empty GameObject for this purpose, and then add a script to it. We want this script to paste the pipe into the world every so often. In order to do this, we have a couple of problems to tackle. First of all, how do we refer to our prefab in the script? Well, our prefab is a type of GameObject, so that will be its type. We can initialise it by adding the snippet “[SerializeField]” at the beginning of our variable declaration. This will let Unity know to add a field to our scripts section of the inspector into which we can drag and drop whichever GameObject we want our variable to refer to.

[SerializeField] GameObject pipePrefab;

Next, we need to keep track of how much time has passed. We can do this by checking the “time” variable of the “Time” namespace, as so:

var currentTime = Time.time;

We can check the time when the game starts, and compare that with the time at the start of each frame to see how much time has elapsed.

float startTime, elapsedTime;

void Start()

{

startTime = Time.time;

}

void Update()

{

elapsedTime = Time.time - startTime;

}

When a certain amount of time has passed, we can paste our prefab into the world and reset the timer.

void Update()

{

elapsedTime = Time.time - startTime;

if (elapsedTime > 3)

{

// Spawn prefab

startTime = Time.time // Reset timer.

}

}

Note: Another common way of tackling time-dependent behavior is by using coroutines. They’re a bit advanced to fit in here, but they’re definitely worth learning about once you’re comfortable with the tools provided by this workshop.

Now to tackle our last problem. How do we paste our prefab? Well, we can do that with the “Instantiate” function, as so:

Instantiate(pipePrefab);

Note: By default, the “Instantiate” function will paste the GameObject into whatever location the parent running the script occupies. If you want to change this, you can provide an additional argument of type “Vector2” to specify a location.

Putting it all together:

using System.Collections;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using UnityEngine;

public class PipeManager : MonoBehaviour

{

[SerializeField] GameObject pipePrefab;

float startTime, elapsedTime;

// Start is called before the first frame update

void Start()

{

startTime = Time.time;

}

// Update is called once per frame

void Update()

{

elapsedTime = Time.time - startTime;

if (elapsedTime > 3)

{

Instantiate(pipePrefab);

startTime = Time.time;

}

}

}

Note: We keep installing new pipes, but we never delete the old ones. This means Unity is still keeping track of all the old ones, which can get more and more computationally expensive as more pipes are instantiated. Instantiate actually returns a value which points to the GameObject it creates. You can use this to keep track of old pipes, and delete (Delete(object)) them when they are no longer useful.

Problem: These pipes are all being instantiated at the same place. Let’s add some random variations to their y-position like so:

var pipe = Instantiate(pipePrefab);

pipe.transform.position += new Vector3(0, Random.Range(-2.5f, 2.5f));

Much better! You should end up with something like this.

Game Over

You may notice that our bird can go right through the pipe! We can remedy this by adding Box Collider 2D components to all of our sprites. The box collider will define the area within your sprite that cannot pass through other sprites. Your result should look something like this

Note: Adding collision to the pipes can be a little tricky. Remember to edit the prefab, rather than whatever’s in the scene hierarchy. Also, remember that we want the box colliders to be on the “children” GameObjects, because they’re the ones with the sprites.

You’ll notice that the objects collide into one another, but we aren’t interested in simulating the collision of two objects… We just want to know when they collide so that we can end the game. Let’s add the following function to the Bird class in our Bird script:

private void OnCollisionEnter2D(Collision2D col)

{

}

This function will be called whenever our bird collides into something, which is when we want the game to end. Typically, when a game ends, the game will stop and some “You Lose!” text will popup on the screen. Let’s implement that. The “timescale” variable of the “Time” namespace is used to describe the rate at which time progresses. By setting it to 0, we can stop the game.

Time.timescale = 0;

Now, for the “You Lose!” text. In the hierarchy panel, we can create some text by right clicking and selecting UI → Text - TextMeshPro. Unity will prompt you to “Import TMP Essentials”. Do so, but you do not need to import the examples and extras - just close the popup.

Note: TextMeshPro (TMP) is an add-on to Unity that provides extra functionality as compared to Unity’s original text objects. Nowadays, TextMeshPro has become the standard that people default to, so we will be using that as well.

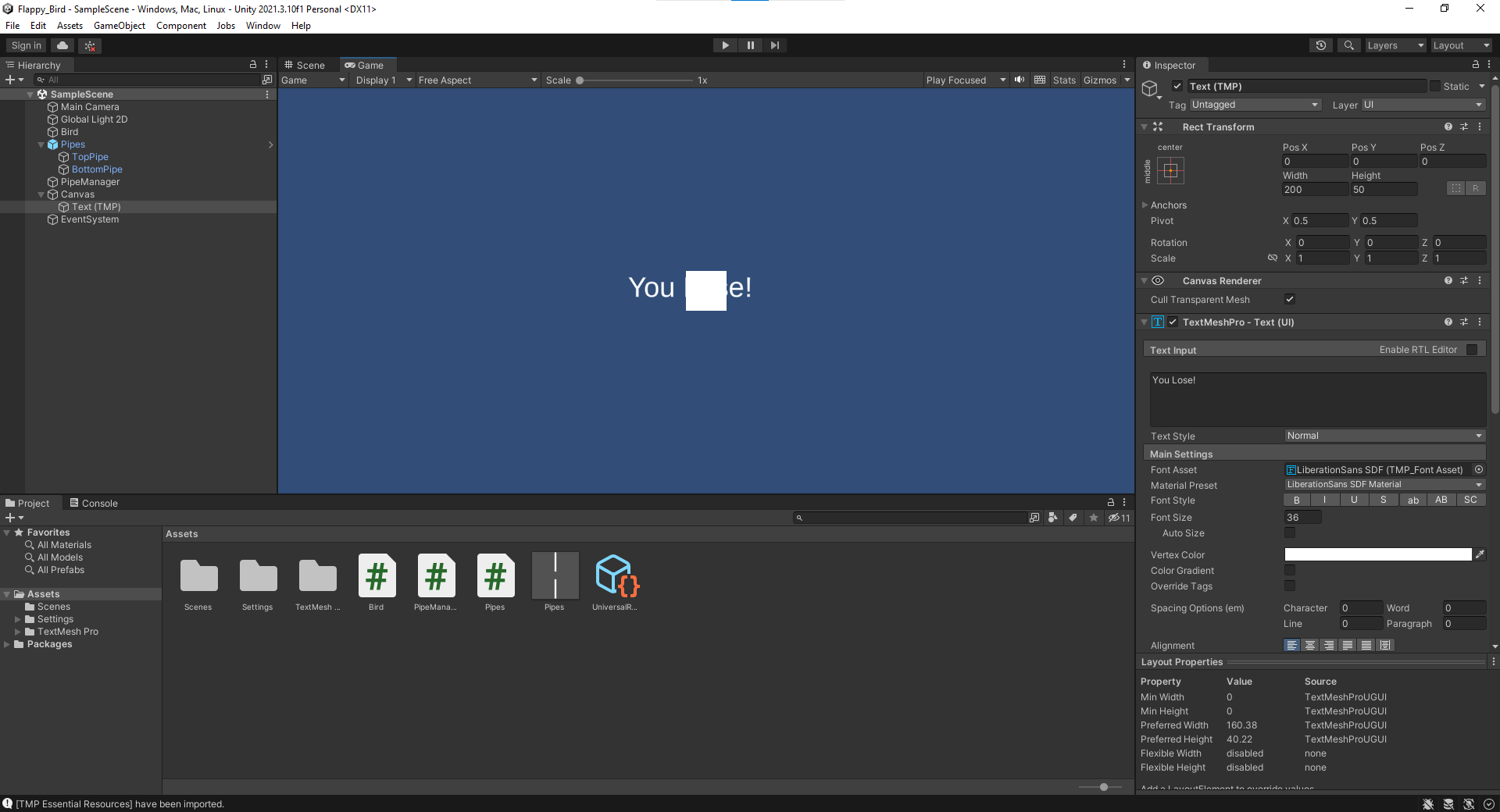

You’ll notice that three things have appeared in your scene hierarchy: EventSystem, Canvas, and Text (TMP). The EventSystem is something that Unity provides to help the user interface register user input. The text is the thing that we intended to create, and the Canvas is a GameObject that all UI in your game world must be a child of. Select the text and centre it by experimenting with the options in the “Rect Transform” component, then edit the “TextMeshPro - Text (UI)” component to make it say “You Lose!”. The game panel should show something like this:

Now, we don’t want the loss text showing up all the time, only when the player loses. We can make it inactive by clicking on the text GameObject and unchecking the box at the top of the inspector. Now it’s invisible! We can reactivate it when the bird collides into something like so:

[SerializeField] GameObject LoseText; // Drag and drop the text into this field in the inspector.

...

private void OnCollisionEnter2D(Collision2D col)

{

Time.timeScale = 0;

LoseText.SetActive(true);

}

Now your “lose text” condition should be working how we want it to!

Keeping Score

Task: You can use what you’ve learnt so far, with a little googling, to implement the score system. You’ll want to:

- Add some text to the screen to indicate the player’s current score.

- Add a collider to the gap between the pipes.

- Set the collider to be a trigger in the inspector. This means that collisions are registered but objects can still pass through.

- Use the “OnTriggerEnter2D” function (analogous to OnColliderEnter2D) to track when the bird enters the gap.

- When the bird enters the gap, find the score text, and set it to display a value one higher than what was displayed there before.

Note: The Unity Documentation will be very useful in finding out more information about functions that you haven’t used before.

You should aim for something like this.

If you’re having trouble, check out the example project in this repo for hints.

Releasing your Game

Building

No one at Spoons will be impressed if you pull out your laptop and show them your project running in the Unity editor - trust me. You’ll want to build it first. Select File → Build Settings and a new window will appear. Here you can select which platform you would like your game to run on. Select Build or “Build and Run” to have Unity package all your code and assets packaged up into a nice .exe file that you can run outside of the editor.

Sharing

Now having your game run in a dedicated window is cool and everything, but what happens when the friends you’ve made at Spoons want to play it on their own time? You’ll need to share your game on a platform that they’ll all have access to. This article explains how to upload your game to itch.io - a popular platform for sharing Indie games.

Feedback

Any issues with this tutorial? Submit an issue or a pull request and we'll get it sorted out right away.